At work there is a tradition of a Friday quiz being posted by the winner of the previous week. I missed out on the most recent one due to having to duck off early to do my tax but the problem was rather an interesting one.

The challange itself is not as simple as you would initally think and taken from a 2015 IBM Ponder This https://www.research.ibm.com/haifa/ponderthis/challenges/May2015.html

Three people are playing the following betting game.

Every five minutes, a turn takes place in which a random player rests and the other two bet against one another with all of their money.

The player with the smaller amount of money always wins, doubling his money by taking it from the loser.

For example, if the initial amounts of money are 1, 4, and 6, then the result of the first turn can be either

2,3,6 (1 wins against 4); 1,8,2 (4 wins against 6); or 2,4,5 (1 wins against 6).

If two players with the same amount of money play against one another, the game immediately ends for all three players.

Find initial amounts of money for the three players, where none of the three has more than 255, and in such a way that the game cannot end in less than one hour. (So at least 12 turns)

In the example above (1,4,6), there is no way to end the game in less than 15 minutes.

All numbers must be positive integers.

Only one person managed to find an answer, lets call him Josh (because that’s his name), having spent a few hours writing up a solution using his favourite programming language Go. Come Monday morning I arrived, looked at the quiz I and became intrigued. Could I write a version that would outperform his. After all Go is a pretty performant language, but I suspected that he may have missed some easy optimisations, and if I picked something equally as fast I should be able to at least equal it.

I took a copy of his code https://gist.github.com/walesey/e2427c28a859c4f7bc920c9af2858492 (since modified to be much faster) with a runtime of 1 minute 40 seconds (on my laptop) started work.

This sort of problem can be pretty easily solved with a brute force solution, which is what Josh has done. They quite often can be more than fast enough and for tight CPU loops modern CPU’s have a great deal of force.

Looking at the problem itself we have a few pieces of information we can use. One is that we don’t ever need to calculate the 12th turn. If the game makes the 11th turn and still continues then it made 12 so that saves us some calculations. Another is that if any money amounts are the same we can stop the game instantlty, and more importantly not even add those to the loop.

Given that the existing solution was written in Go it seemed insane to some that I started writing my solution at least initally in Python. This however is not as crazy as it seems. Python being higly malleable allow some rapid iteration, trying out a few things before moving over to another language.

The first thing to note is that you need to generate a tree of every possible combination that a game can take. Then you iterate over each one for the inital starting amounts of money to determine if the game ever ends, and if not mark it as a game that does not finish. To generate the combinations I went with a fairly simple recursive strategy,

# Calculate all the possible sequences for who misses out for each turn

def calc_events(current=[], turn=0):

if turn == DESIRED_TURNS:

return [current]

one = list(current)

one.append(0)

two = list(current)

two.append(1)

three = list(current)

three.append(2)

turn += 1

path1 = calc_events(current=one, turn=turn)

path2 = calc_events(current=two, turn=turn)

path3 = calc_events(current=three, turn=turn)

return path1 + path2 + path3The result of running the above is an array of arrays containing each situation where someone sits out a turn. It is important to note that his produces a list that modifies from the back (big-endian so to speak) as this will be a very important consideration later.

The result looks something like this (truncated to just 4 results),

[0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0]

[0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 1]

[0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 2]

[0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 1, 0]Given the above I coded up a simple solution which simply looped through the combinations. Here it is in pseudocode.

for player1 money:

for player2 money:

for player3 money:

for game in games:

for turn in game:

result = play turn using money amounts

if result:

print player1, player2, player3The above is about as bad as it gets for an algorithm as we have 5 nested loops. As expected the runtime performance was horrible. In fact I added a progress bar which simply calculated how far into the first loop the application had reached. Using Python I worked out that it was going to take several hours to get a result using the above. Not good enough.

A few calculations and I realised that I was asking my poor program to calculate something like 50 billion games. Clearly I needed to reduce the number of games and speed up the processing as much as possible. The first change I made was to only calculate the game turn events once and keep the result. I had also written the code to be as readable as possible, which how you should write anything but as this can be an issue also removed the following function by inlining it for improved performance.

def turn(p1, p2):

if p1 == p2:

return False, p1, p2

if p1 > p2:

p1 = p1 - p2

p2 = p2 + p2

else:

p2 = p2 - p1

p1 = p1 + p1

return True, p1, p2The next thing I did was generate all the permutations of money amounts to play games with into a single list. The last thing I did was switch from using Python to PyPy which with its JIT should speed up the loops considerably. The result of all this can be found here https://gist.github.com/boyter/cab749f4713201f5b409c5b1353fc36c and its runtime using PyPy dropped to ~8 minutes.

8 minutes was about 5 times slower then the GoLang program at this point, which is pretty good for a dynamic language like Python, and consider that my implementation was single threaded where as the Go was using as many cores as it could get. In fact thinking about that, I was running Josh’s code on a 4 core machine which means that the PyPy solution was almost as fast per core. This really tells volumes about the PyPy project.

My next step was to implement the same program in a faster language. The only other faster languages I know that I have any experience in are C# and Java. Since I already had Java setup I went with that. I will also admit it was about proving a point. Go may be fast, but at time of writing Java should be able to equal it for most tasks.

However I mentioned to Josh that his Go program had some inefficiencies. The big one being that he was calculating the 12th game needlessly. I then modified his program and with some other changed reduced the Go program runtime down to ~40 seconds. I was starting to get worried at this point, as I was aiming to beat the Go program’s performance by 5%. No idea why I picked this number but it seemed reasonable if I was smart with the implementation.

At first I ported the Python program in its original readable reusable form to Java and ran it. The runtime was ~7 minutes. I then inlined the same functions and converted it over to use parallel streams. This time the runtime was about 90 seconds. This would have been fast enough had I not mentioned to Josh how he could improve his code. I had shifted the goalposts on myself and had a new target now of ~40 seconds.

After doing a few things such as inlining where possible, changing to enum and some other small tweaks I had a runtime of ~60 seconds. The big breakthrough I had was after looking at the hot function I realised that storing the game events in a List of Arrays meant that we had a loop in a loop. It was however possible to flatten this into a single array of integers and reset the game every 11 turns with a simple if check.

This was the breakthrough I needed. Suddently the runtime dropped from ~60 seconds to ~23 seconds. I happily posted my success in the Slack channel with a link to the code and sat back.

The smile was soon turned to a frown. Josh implemented the same logic into his Go program and it now ran in ~6 seconds. It was suddently 5x times faster. At this point I had a mild panic and started playing with bitwise operations and other micro optimisations before realising that no matter what I did he could simply implement the same change and get the same performance benefit as we were both using roughtly the same algorithm.

Something was clearly wrong. Either Go was suddently 5x faster at a basic for loop and integer math then Java OR I had a bug in my code somewhere which was making it worse. I looked. Josh looked. A few other people looked. Nobody could work out what the issue was. At this point I didn’t care about the runtime, I just wanted to know WHY did it appear to be running slower. I was so desperate for an answer I did what all programmers do at this point and outsourced to the collective brain known as Stack Overflow http://stackoverflow.com/questions/43082115/why-is-this-golang-solution-faster-then-the-equivalent-java-solution

A few un-constructive comments came back such as Java is slow (seriously it is not 1999 anymore guys, Java is fast) etc… Thankfully one brilliant person managed to point out what I had missed. It was not the loop itself, but the input. Remember how I said that the generation of the events being big-endian was important? Turns out the Go program had done the reverse and implemented it little-endian.

The thing about the core loop is that it has a bail-out condition. If two players have the same money amount we end the game and don’t process any further. The worst possible situation for the loop is to process almost every condition only to find out just at the end that it ended. It is a lot of wasted processing work. Ideally you want to find the failing conditions as soon as possible. By changing the games from the end I was forcing the Java program to process about 5x times as many combinations as the Go program.

It just happended to be that Josh has picked a more optimal path through the games.

A simple reverse of the games (line 126 of the linked solution) and suddenly the Java program was running in about ~6 seconds and the same time as the Go program. You can view the code where https://gist.github.com/boyter/42df7f203c0932e37980f7974c017ec5

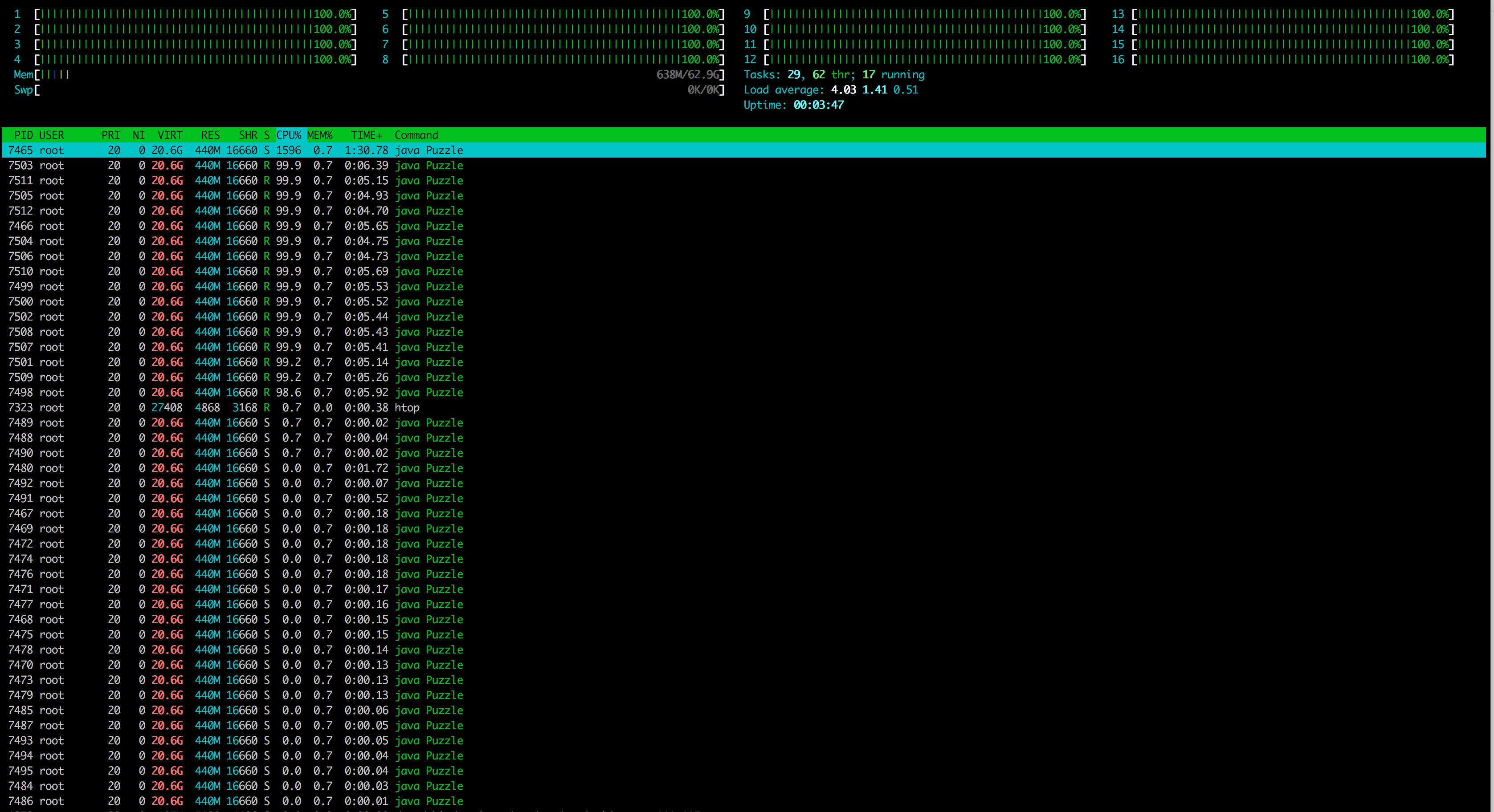

For fun I tried running it on a 16 core VPS and it ran in about ~2 seconds and maxed out all the cores so it seems parallel streams do what you expect them to.

Interestingly while Josh’s starting positions was more optimal then mine, its probably still not the optimal path for this problem. There is bound to be a way to generate the games such that you hit the failing conditions as soon as possible saving needless processing. There is probably a Thesis for a PhD in there somewhere.

I figure this is probably as far as I want to take this. I did play around with bitwise operations and loop un-rolling but the time didn’t change that much.

I certainly had fun with the implementation and working things out. Some may argue that optimising for a micro benchmark such as this is a waste of time, and generally they would be right. That said there are occasions where you really do need to optimise the hell out of something, say a diff algorithm or some such. In any case what developer does not dream of saving the day with some hand unrolled loop optimisation that saves the company millions and brings the developer the praise and respect of their peers!

EDIT – A rather smart person by the name of dietrichepp pointed out that there is a better algorithm. Rather than brute force the states work backwards. You can read their comment on Hacker News and view their code in C++ on Github.