It started with this chain of blog posts,

Using Java to Read Really, Really Large Files -> Processing Large Files in Java -> Processing Large Files – Java, Go and ‘hitting the wall’

I thought after reading them I would add to the chain.

While I don’t like solving arbitrary company made “programming tests” when doing interviews https://boyter.org/2016/09/companies-recruiting/ whenever I see a post comparing Go to Java where Java is trounced in performance gets my attention. Unless its a very short lived command line application where JVM startup is a problem or some super optimized Go solution in my experience so far Java should generally be slightly faster. The computer language benchmarks tend to show the same result so its not a flight of fancy for me.

I had a look through Marcel’s solution compared to Paige and Stuart’s and it was fairly obvious that the Go solution was going to be faster since it made a good use of Go routines and channels.

Which made me think. While I understand that Go channels are effectively a BufferedQueue (with size of 1 in the case of unbuffered) with some synatic sugar, I had never actually tried writing Java using that technique. Processing a very large file with one thread reading and other threads processing is pretty much the textbook solution to solve this problem and as such Go’s concurrency plays very nicely into this.

Since I didn’t have any experience with a direct Go to Java comparison I figured it would be a good thing to play around with.

I took a copy of Marcel’s optimal Go solution, pulled down the sample set and tried it out. The sample set linked https://www.fec.gov/files/bulk-downloads/2018/indiv18.zip when un-zipped needed to be concatenated together into the file itcont.txt which when done was about 4 GB in size at time of writing. This was larger than what the other posts were working with so I then compiled the optimal solution and ran it.

$ time ./go-solution itcont.txt > /dev/null

./go-solution itcont.txt > /dev/null 14.14s user 6.52s system 222% cpu 9.296 total

My first thought was is this actually an optimal time? I know from playing with memory mapped files with scc that if the file is large such as the one in this case there are massive wins to be gained using them. Turns out that ripgrep uses memory mapped files, so we can use it to see how fast you can actually read the file.

Asking wc to just count newlines should also allow it to go about as fast as possible, and if we get ripgrep to invert match over everything it will match nothing but read the whole file. I know for a fact that for a single large file ripgrep will flip to memory maps, and I threw wc in there because I assume it would do the same.

$ hyperfine -i 'rg -v . itcont.txt' 'wc -l itcont.txt'

Benchmark #1: rg -v . itcont.txt

Time (mean ± σ): 2.592 s ± 0.046 s [User: 1.375 s, System: 1.216 s]

Range (min … max): 2.560 s … 2.624 s

Benchmark #2: wc -l itcont.txt

Time (mean ± σ): 2.679 s ± 0.141 s [User: 413.8 ms, System: 2262.7 ms]

Range (min … max): 2.579 s … 2.778 s

The above is a stupid thing to ask ripgrep to do, which is match everything but invert so nothing matches, but it should read every byte in the file. Turns out Marcel’s solution is not as optimal as he would have believed. One catch however is that there is no easy way to match ripgrep or wc’s implementation using Java. The reason is that memory mapped files in Java don’t really work. The Java standard library maps to a ByteBuffer which is limited to 2^31-1 bytes which means it won’t work on a file over 2 GB in size. You can abstract over this to map larger files, but I am not in the mood to put that much effort into a toy problem.

Some further reading on the issue,

- http://nyeggen.com/post/2014-05-18-memory-mapping-%3E2gb-of-data-in-java/

- https://howtodoinjava.com/java7/nio/memory-mapped-files-mappedbytebuffer/

- https://stackoverflow.com/questions/41324192/why-is-bufferedreader-read-much-slower-than-readline

- http://www.mapdb.org/blog/mmap_files_alloc_and_jvm_crash/

- https://news.ycombinator.com/item?id=3428357

- http://vanillajava.blogspot.com/2011/12/using-memory-mapped-file-for-huge.html

So that said, lets see if we can get close to the time of the “optimal” Go solution.

The first thing to do is create a simple Java application which reads through the file. This is to give some baseline performance of file reading in Java and I would hope is about the same as the Go code. A very simple way to do this is include below.

import java.io.BufferedReader;

import java.io.IOException;

import java.nio.file.Files;

import java.nio.file.Path;

public class FileRead {

public static void main(String[] argv) {

var lineCount = 0;

try (var b = Files.newBufferedReader(Path.of("itcont.txt"))) {

var readLine = "";

while ((readLine = b.readLine()) != null) {

lineCount++;

}

} catch (IOException ignored) {

}

System.out.println(lineCount);

}

}Then the result when running.

$ time java FileRead > /dev/null

java FileRead > /dev/null 6.11s user 3.69s system 106% cpu 9.221 total

The same result as the Go. This indicates that the Go code as mentioned by Marcel is indeed bottlenecked by how its reading from the disk and not by the CPU. So long as when processing we don’t Go below this number we know we have an equally optimial solution.

So with that done I quickly implemented the requirements which are,

- Write a program that will print out the total number of lines in the file.

- Notice that the 8th column contains a person’s name. Write a program that loads in this data and creates an array with all name strings. Print out the 432nd and 43243rd names.

- Notice that the 5th column contains a form of date. Count how many donations occurred in each month and print out the results.

- Notice that the 8th column contains a person’s name. Create an array with each first name. Identify the most common first name in the data and how many times it occurs.

With that implemented a quick test to see how much this has impacted the performance.

$ time java FileProcess > /dev/null

java FileProcess > /dev/null 99.38s user 15.53s system 245% cpu 46.893 total

Quite a lot. It makes sense though because we added processing of the lines, rather than just reading them. With the file consisting of 21,627,188 lines it means its taking 0.00000212695 seconds to process each line which is about 2100 nanoseconds.

Using Go, what would happen is to pump those lines into a channel and process them using some Go routines. As mentioned we can do the same in Java using a Queue and some threads. To begin with though I thought it would be worthwhile to try with one thread processing a queue just to see if we get any gains.

To implement a Go channel like structure in Java you need a thread safe queue which when you want to close you add a poison value which tells the processing threads to quit.

With the task configured and running the loop becomes like the below,

processor.start();

try (var b = Files.newBufferedReader(Path.of("itcont.txt"))) {

var readLine = "";

while ((readLine = b.readLine()) != null) {

lineCount++;

queue.offer(readLine);

}

queue.offer(poison);

}

processor.join();I than ran the above to see what gain, if any, was delivered.

$ time java FileThreadProcess > /dev/null

java FileThreadProcess > /dev/null 48.36s user 16.91s system 346% cpu 18.862 total

A massive improvement over the single threaded process. However its still slower than the time to read from disk without doing any processing.

With the above reading of the file should be only blocked by how quickly the background thread can process the queue. One way to check this is by printing out the queue length every now and then by adding a modulus check of the lineCount and a println.

if (lineCount % 100000 == 0) {

System.out.println(queue.size());

}The result of which showed the following,

974

987

984

992

960

885

996

Suggesting that the single thread was unable to keep up with the reading off disk. A reasonable guess at this point would be to spawn another thread. Doing so is faily trivial with some copy paste, but we also need to make all of the shared data structures thread safe.

var names = Collections.synchronizedList(new ArrayList<String>());

var firstNames = Collections.synchronizedList(new ArrayList<String>());

var donations = new ConcurrentHashMap<String, Integer>();In the above a ConcurrentHashMap is much faster than a syncronised map as it has smarter locking under the hood.

With that done I added another thread and ran the process and got the following output.

96

0

4

0

11

12

1

Which suggests that 2 threads processing the queue is enough to keep up with the disk. Now to try it out,

$ time java FileThreadsProcess > /dev/null

java FileThreadsProcess > /dev/null 69.20s user 29.03s system 329% cpu 29.842 total

What the? Thats about twice as slow as the version which had a single thread processing the queue! The queue is being emptied faster which shouldn’t block the reader but somehow its slower? That does not appear to make sense.

My guess would be that either the Queue we are using is not very efficient or we are asking it to do too much. Since we already know that the two threads can keep up with the file read (on this machine) I decided to swap it out for a LinkedTransferQueue which is not bounded but should be faster due to less locks to prove the theory.

$ time java FileThreadsProcess > /dev/null

java FileThreadsProcess > /dev/null 66.50s user 23.95s system 419% cpu 21.563 total

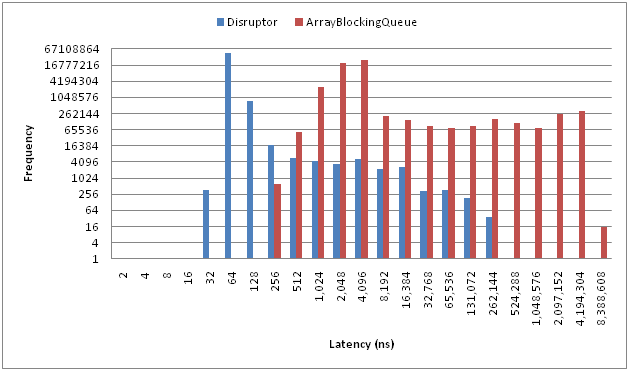

The runtime dropped by almost 1/3 which proves that indeed the queue is now the bottleneck. At this point we have two options. The first is to find a faster queue implementation, and the second is to be more effective with how we use the queue. Since I wanted to stick to the native libraries I decided to be more effective with the queue. The overhead of the queues in Java are will known hence projects like Disruptor existing. You can see the latency cost of the ArrayBlockingQueue in the latency chart they supply.

Seeing that the queue has 256 ns of latency fits in well with the numbers we had when running multiple threads and explains why it was actually slower as we were doing two calls to the queue per line.

Since I wasn’t looking to swap out the queue implementation I tried to make it more efficient. To reduce the latency in this case one easy solution is to batch the lines together into lists and then have the worker thread process those. It means less calls to the queue. With 256 ns of latency per call, batching them into chunks of 10,000 lines is going to save 2 ms of processing time. Given there are about 2100 chunks in the file at this size that works out to be about 4.2 seconds of saved processing time. We can then tweak the size of the batch to see what is optimal for this task.

So with the above done we end up with something like the below with the processing removed for brevity,

import java.io.IOException;

import java.nio.file.Files;

import java.nio.file.Path;

import java.time.Duration;

import java.time.Instant;

import java.util.*;

import java.util.concurrent.ArrayBlockingQueue;

import java.util.concurrent.ConcurrentHashMap;

import java.util.function.Function;

import java.util.stream.Collectors;

public class FileReadChallange {

private String FILE_NAME = "itcont.txt";

private int WORKERS = 2;

private int BATCH_SIZE = 50000;

private String POISON = "quit";

private ArrayBlockingQueue<ArrayList<String>> queue = new ArrayBlockingQueue<>(1000);

private int lineCount = 0;

private List<String> names = Collections.synchronizedList(new ArrayList<String>());

private List<String> firstNames = Collections.synchronizedList(new ArrayList<String>());

private Map<String, Integer> donations = new ConcurrentHashMap<String, Integer>();

public static void main(String[] args) throws IOException, InterruptedException {

var m = new FileReadChallange();

m.run();

}

public void run() throws IOException, InterruptedException {

var threads = new ArrayList<Thread>(this.WORKERS);

for (int i = 0; i < this.WORKERS; i++) {

var processor = new Thread(this::processLines);

processor.start();

threads.add(processor);

}

try (var b = Files.newBufferedReader(Path.of(this.FILE_NAME))) {

var readLine = "";

var lines = new ArrayList<String>();

while ((readLine = b.readLine()) != null) {

this.lineCount++;

lines.add(readLine);

if (this.lineCount % this.BATCH_SIZE == 0) {

this.queue.offer(lines);

lines = new ArrayList<>();

}

}

var poisonList = new ArrayList<String>();

poisonList.add(POISON);

for (int i = 0; i < this.WORKERS; i++) {

this.queue.offer(poisonList);

}

}

for (var processor : threads) {

processor.join();

}

}

private void processLines() {

try {

while (true) {

var lines = this.queue.take();

if (lines.size() == 1 && lines.get(0).equals(POISON)) {

return;

}

for (var line : lines) {

var split = line.split("\\|", 9);

this.names.add(split[7]);

var ym = split[4].substring(0, 6);

if (this.donations.containsKey(ym)) {

// NB this is not thread safe! Didn't bother fixing

this.donations.put(ym, this.donations.get(ym) + 1);

} else {

this.donations.put(ym, 0);

}

this.firstNames.add(this.extractFirstName(split[7]));

}

}

} catch (InterruptedException ignored) {

}

}

private String extractFirstName(String line) {

var inName = false;

var sb = new StringBuilder();

// To get the first name loop to the first space, then keep going till the end or the next space

for (var c : line.toCharArray()) {

if (c == ' ') {

if (inName) {

return sb.toString();

}

inName = !inName;

} else {

if (inName) {

sb.append(c);

}

}

}

return sb.toString();

}

}And when I ran it locally,

$ time java FileReadChallange

java FileReadChallange 48.25s user 20.45s system 412% cpu 16.647 total

Still not as optimal as the Go solution but much better than where it started.

Knowing that no matter what I did at this point it still was not going to be the optimal solution due to the state of memory mapped files I lost interest. However I did find it a good exercise to implement Go like concurrency in Java. Given a little more effort I am confident I could match the Go time, however it would feel like a hollow achievement knowing that the true processing time could be.

Some people have correctly pointed out that the solution is not thread safe. I never bothered fixing it due to having given up due to the lack of access to OS primitives such as a proper mmap. In short, if you need to process large files off the disk as quickly as possible Java is probably not the right choice. There are a bunch of optimizations that could be included in the above code to drop the runtime as is though. The catch being they are a local optimum and I would not find that satisfying.

Maybe one of these days I will find a good memory map implementation for Java and revisit it. Either that or I will continue to work with Rust or try things out using Zig or V Lang.

EDIT - As predicted someone did come along and throw together a Rust implementation which using memory mapped files is much faster https://github.com/arirahikkala/donationcount and Davide has improved on the Java version using Futures https://gist.github.com/dfa1/65ae63ca3f10a72e57885add52c48b4f to lower the runtime to ~10 seconds bringing it in line with the Go version.