Abstract TL/DR

I present what I belive is a unique index for indexing and searching source code. It copies ideas from Bing bitfunnel implementation to create a very fast, memory efficient trigram index over source code.

- searchcode.com is now using a custom built index written by yours truly

- It indexes 180-200 million documents and 75 billions lines of code

- The index works using bloom filters sharded by unique document trigrams

- It borrows some of the core ideas of bitfunnel used in microsoft’s bing

- The use of trigrams inside a bloom filter search is as far as I can tell unique

- It lowered the index search times from many seconds to ~40ms across searchcode

- End user searches still take around 300 ms to process though

- It also improved search relevance and reliability

- Architecture wise things became simpler, as the new index sits on a single machine not four

- It uses caddy as the reverse proxy and redis as a level 2 cache

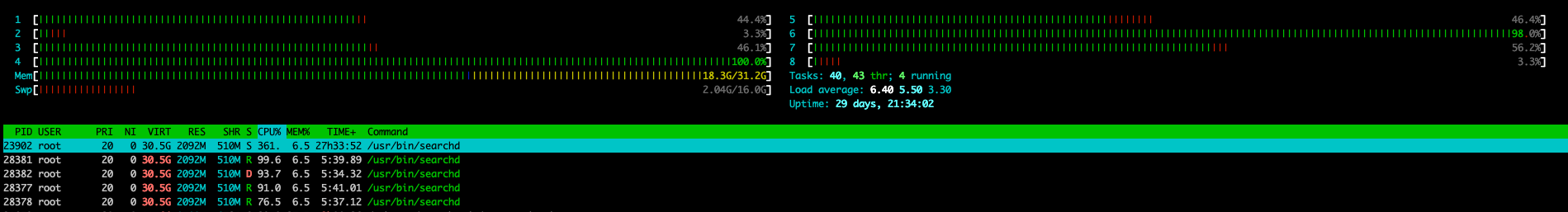

- The index sits entirely in memory on a 16 core 5950x CPU and 128 GB RAM machine

- It currently processes close to a million searches every day

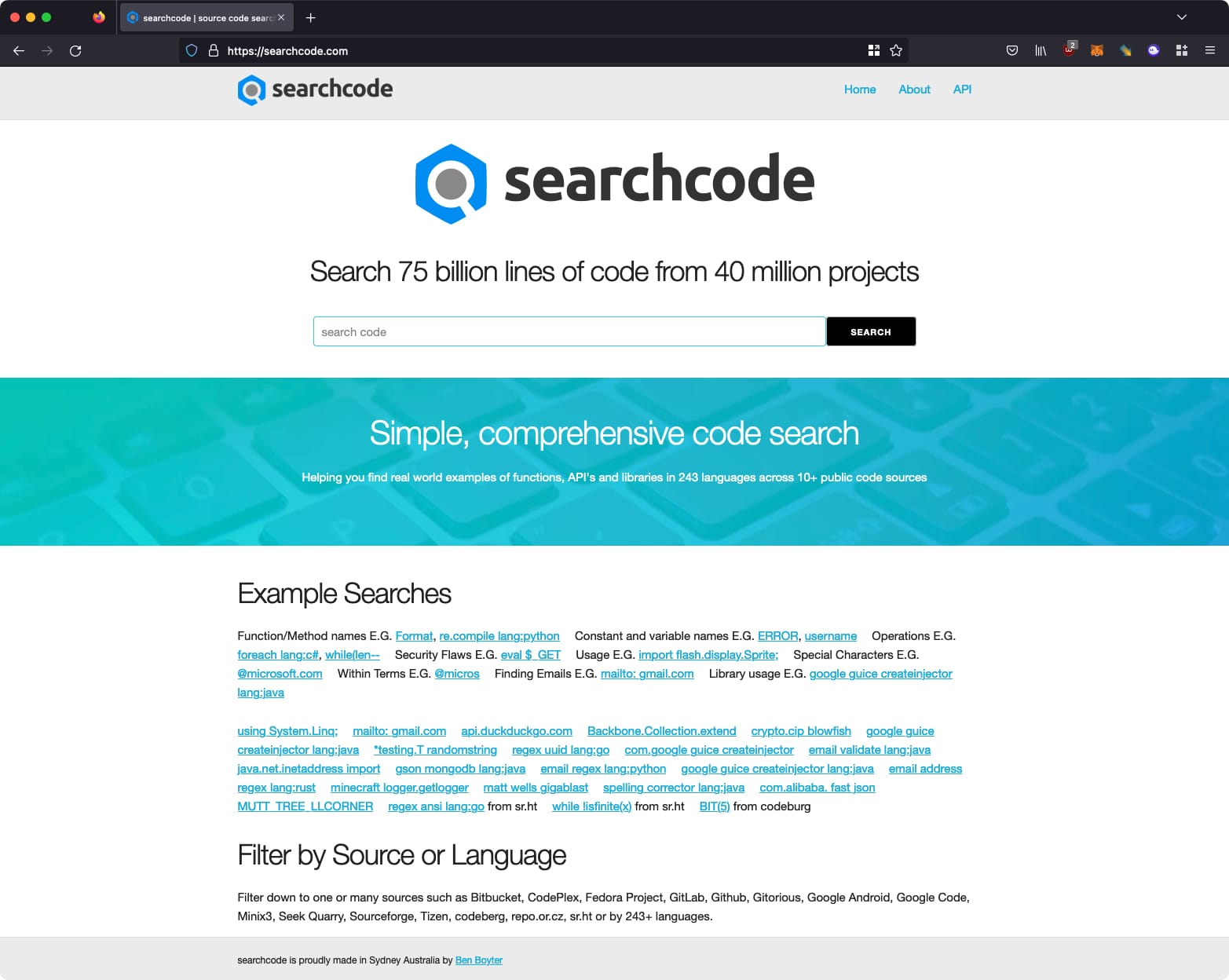

- I also gave the site a new look and feel which is much better than what it looked like previously

- I had an absolute blast learning and building it

What Happened?

On Monday 21st November 2022 I updated the DNS entries for searchcode to point at the new searchcode server running a custom implemented index, ending the reliance on sphinx/manticore in order to power searches. Since being released I have observed it run over 1 million searches a day with a rolling average runtime of ~40 ms for replacement index.

Sometime during the 2020 lock downs when I commented on the company slack that I should build my own custom index for searchcode. A few responded encouragingly that if anyone can do it it was me. While I appreciated their confidence I didn’t do anything until hiking with a mate sometime in 2021 where after a few beers at the end of the day I brimming with confidence laid out my plan of attack.

I had felt like a fraud for a while. I get a lot of questions about indexing code and my answer has always been that I use sphinx search. Recently that has changed, as I moved over to its forked version manticore search. Manticore is an excellent successor to sphinx and I really do recommend it.

However, using the above is me outsourcing the core functionality of searchcode to a third party, and I strongly believe you shouldn’t outsource your core competency. So I thought I should really try to do this myself. Besides, I knew I would really enjoy this process and so a few days later I started work.

The result of my effort can be viewed at searchcode.com and looks like the below.

A little over a year’s worth of effort and I can now talk/write about it. I consider it the pinnacle of my development career to date, and I am very proud of my achievement. Feel free to read further if you would like to learn how I did it, what I was thinking etc… What follows is a collection of my development thoughts and ideas.

Development Thoughts

What follows are my thoughts I kept as I implemented things. Included so I have something to look back on, and perhaps someone will find it useful. It might be a bit disjointed as a lot of it was written as I was building things.

The Problem with Indexing Source Code

So why even build your own index? Why would anyone consider doing this when there are so many projects that can do this for you. Off the top of my head we have code available for lucene, sphinx, solr, elasticsearch, manticore, xaipan, gigablast, bleve, bludge, mg4j, mnoGoSearch… you get the idea. There are a lot of them out there. Most of them however are focused on text and not source code, and the difference when it comes to search is larger than you might expect.

It’s also worth noting that the really large scale engines such as Bing and Google have their own indexing engines. Partly because it gives you the ability to wring more performance out of the system since you know where you can cut corners or save space, assuming you have the skill or knowledge.

I guess the saying “the thing about reinventing the wheel is you can get a round one” applies here. By implementing my own solution I could ensure I get something that works within the bounds of what I need.

So searching source code. I have written about this before, but consider the following,

A query term,

i++and then consider the following code snippets which contain a match,

for(i=0; i++; i<100) {

for(i=0;i++;i<100) {How do you split them into terms? By spaces which is what most index tools do (for English language documents) which results in the following,

for(i=0;

i++;

i<100)

{

for(i=0;i++;i<100)

{None of the terms match our term i++ unless you start doing wildcard searches.

This is something I worked around in searchcode for years, by splitting the terms myself such that the search i++ would work as expected. This was done by replacing characters such as { with spaces, and then splitting on those spaces, feeding those tokens into the index, then replacing other characters and repeating.

We also need to index those special characters. If someone wants to search for for(i=0;i++;i<100) there is no good reason to not allow them to do so. As such I had to configure sphinx/manticore to index these characters, which isn’t natural to them and breaks the query parser.

One way to get around the above is to index ngrams, and more specifically trigrams. This is how Google Code Search worked back in the day. This technique has a few downsides. The first is you end up with really long posting lists. Usually compared to keywords it’s 4-5 times the number of words to index. They also produce false positive matches, because hello when turned into trigrams has the same trigrams that helow yellow, meaning your index reports it as a match when in fact it isn’t.

You can solve the false positive match issue using a positional index, but that brings its own problem. Mostly space. Storing the trigram positions for all of the trigrams in the documents can make your index larger on disk than the thing you are indexing.

So while sphinx/manticore/elastic or any other tool really are excellent. I really want to build my own index. Mostly because of the technical challenge. Secondly because I think I can improve on how searchcode works with a deep level integration. Lastly because I doubt I will ever get to work on a large scale web index (it’s just too expensive to do by yourself these days, and I doubt Google or Microsoft are that interested in me personally). This gets me close to living that dream.

Also on occasion I get something like this, which is the manticore/sphinx process going a little crazy due to the amount of searches I had running, and the abuse I put it through.

For the record I do not have a PhD in applied search or any real world experience building web indexes. I don’t even work in the space professionally. Nor am I ever likely too since I doubt what I am presenting here holds a candle to the work of Google/Bing/Facebook Search or any other work by companies who work on these problems full time.

I can use elastic search pretty well though! Really I’m just some dude who grew up in Western Sydney (that’s considered the bad side of Sydney) and apparently dreams about flying close to the sun. Clearly I have no business writing my own indexer. But the nice thing about the internet is you really don’t need permission to do a lot of things, so let’s roll up our flanno sleeves and get coding.

Take anything below with a massive grain of salt before you implement or start hurling internet abuse at me. This is about how I built an index, and not about how you should build one.

Listing down the “requirements” and constraints we have.

Requirements

- We don’t need to support wildcard queries or OR search, AND by default but be able to implement them later…

- We need to be able to search special characters

- We want to be able to update quickly as its a write heavy workload

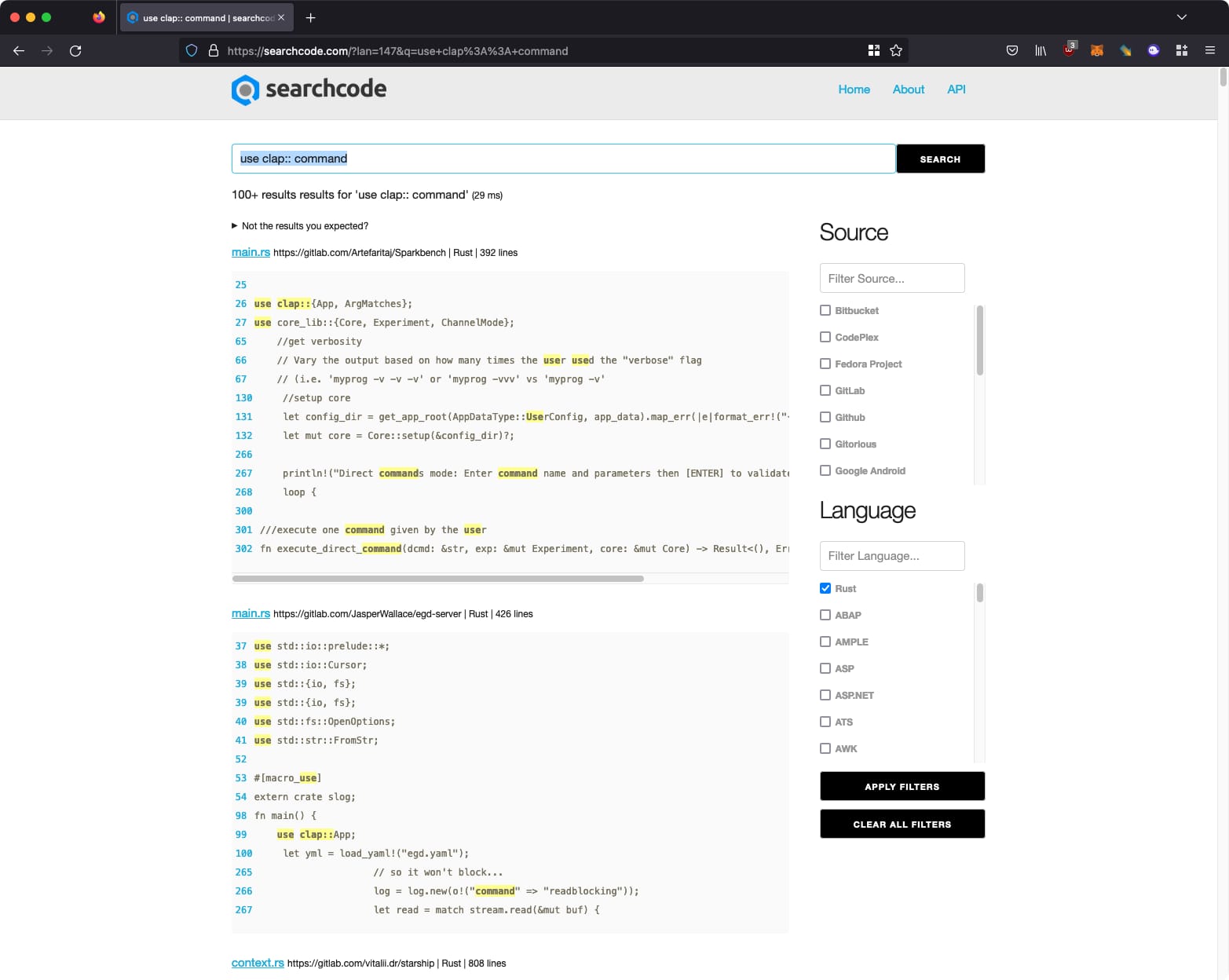

- We need to support filters on source (github/bitbucket etc…) and code language

- It’s a free website, so we can deal with some downtime or inaccuracy

- We want searches to process in a 200 ms time budget with no cache (lower is better though)

- Want to embed into searchcode itself to avoid expensive network calls

- We want to store the entire index in RAM, since RAM is cheap (so they say…)

- We don’t need to do any term rewriting (where you map NY to new york and or search for both)

Constraints

- We have a higher that normal term count per document than normal web content

- We are using Go so we have to think about the impact of the garbage collector

- This is a side project, so whatever is done needs to be achievable by a single person who works on this in their spare time

- We are not going to release this as open source, because if someone wants it they can pay for a copy dammit

Why use Go I hear you ask? Why not C++/Rust/C/Zig! I know 3 languages reasonably well. Those being Java, C# and Go. The current version of searchcode.com is written in Go which is the main reason for using it. Blekko back in the day was supposedly written using Perl so I don’t think performance should be an issue here. Plus I would really like to get this embedded into the application itself to avoid those pesky slow network calls.

It might surprise some reading this to learn that searchcode.com is the work of one person in their spare time. As such I write this pretty frankly. There is no money to be made in the free online code search market (just ask Google or Ohloh), so by all means feel free to take what’s here and enter the “market” and lose money as well. There is a market in enterprise search though, so feel free to compete with sourcegraph if you like.

Note that the point about it being a free service and that we can deal with some downtime influences the design in a lot of ways, which will be covered later.

So there are a few ways to search across content or build an index that I am aware of. Let’s discuss each in term with its advantages and disadvantages

Brute Force

Brute Force, note that this isn’t an index strategy per say, but worth discussing anyway. Assuming you can get the entire corpus you are searching into RAM it is possible to brute force search. I’m including it here so I have the advantages and disadvantages, but suffice to say I have about 30 GB of RAM I can use to hold the index (note this is now 128 GB but still too small), which is nowhere near enough to hold the searchcode corpus. That said the problem is pretty brute forcible given enough CPU and RAM. Note that I do not have enough CPU/RAM to achieve this.

Advantages

- 100% space efficient (for the index anyway) since there isn’t one

- Easy to query/write

- Can determine TF easily as its a positional “index”

- Scales (assuming you are prepared to pay)

- Constant performance

Disadvantages

- Slow… at scale if you cannot fit your corpus in RAM

- Harder to scale because gotta duplicate all the data

- Writing high performance string searches is a very hard problem

Inverted Index

Inverted index. This is pretty much building a map/dictionary of terms to documents and then intersecting them and ranking. One issue with this technique is that you end up with enormous term lists, known as posting lists for common terms. We cannot use stop words to reduce this because we need to index all the content as trigrams, meaning we will get huge posting lists.

Advantages

- Easy to query

- Does not miss terms

- Can easily store term frequency alongside terms creating a positional index

- Fast and easy; intersecting posting lists is something you can hand off to your most junior developer (at least initially)

- Query execution time is related to the number of returned results

Disadvantages

- Hard to update documents usually have to rebuild the index or do delta + merge strategy

- Need to implement skip lists or compression on the posting lists at scale

- Queries can be slow due to the complexity of the list structures

Trie

Trie for example https://github.com/typesense/typesense which uses Adaptive Radix Tree https://stackoverflow.com/questions/50127290/data-structure-for-fast-full-text-search

Advantages

- Constant lookup time

- Potential to be space efficient if key terms share the same prefixes

- Easy to do wildcard queries

- Can store TF alongside terms as a positional index

Disadvantages

- Can take up more space if lots of prefixes

- Not friendly to GC due to the use of pointers (problem for Go)

- Need to implement skip lists or compression on the posting lists at scale

Bit Signatures

This is something I remember reading about years ago, and found this link to prove I had not lost my mind https://www.stavros.io/posts/bloom-filter-search-engine/ At the time I thought it was neat but not very practical… However then it turns out that Bing has been using this technique over its entire web corpus http://bitfunnel.org/ https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1-Xoy5w5ydM

Advantages

- Stupidly fast if careful (bitwise operations are almost free from a CPU point of view)

- Space/Memory efficient

- Easy to update/delete modify existing terms

- Reasonably simple algorithms to code (good for one person)

Disadvantages

- Cannot store term frequency information along terms as its a non-positional index

- Produces false positive matches

- Query execution time is linear in the collection size (bitfunnel is about reducing this to an extent)

- Memory bandwidth of the machine limits how large the index can grow on a single machine

- Done poorly has to process the entire index

Inverted Index Calculations

So with the above I had a further thought and decided I should try either an inverted index, a trie or bit signatures, in roughly that order.

Inside searchcode there are about 300 million code files (as I write this). Ignoring duplicates gives around 200 million or so that we want to search, broken up by about 240 languages across 40 million repositories (these numbers are always growing).

There is probably about 5kb of code in most of those files, with each having about 1000 unique trigrams. This gives us about 1.5 TB of code, which is actually fairly close to what I saw on disk. To verify this I wrote a simple program to loop through the data. This showed about 1320 unique trigrams per document which is bearing up to my back of napkin calculations.

So given our rough numbers, we can work out roughly how large the indexes might need to be. I’m going to ignore most of the overhead of the implementation and just use the known sizes for this. In other words i’m going to assume a map, slice or other data structure is free for these estimates although that is far from the case.

For the inverted index we need in effect a large map of string to integer arrays, representing a word and which documents have it. That’s the bare minimum to work. Any advanced index is compressing the integer arrays somehow, such as Elias-Fano, and is using a skip list allowing you to step through it very quickly.

So let’s assume there is a “free” mapping of strings to integers somewhere allowing us to use an integer for the words. We don’t have one but for the moment while working things out let’s assume so. Let’s also assume we have less than 4 billion terms (I think Bing/Google have something like 10 billion per shard but we are simplifying here) so we can use a 32 bit integer to save some space.

We can store this information, mapping terms (as an integer) to an array of documents containing that term.

map[uint32][]uint32So we now know we need 4 bytes to store each term per document.

So for our example document of 1320 unique trigrams per document, to store it in the index takes 500 * 4 bytes, 5280 bytes. For our 200 million documents that’s 1056000000000 bytes which is about 1000 GB.

Ouch.

That is not going to fit into our RAM budget, which is less than 128 GB.

To confirm my numbers I had a look at the manticore index searchcode was using, and you know what? It was about that size spread across two machines. So our estimates are pretty close, although manticore probably compresses the posting lists. Assuming basic gzip compression over a collection of int’s you can probably reduce the size by 30% which is still way over our RAM limit.

It gets back to that issue that source code tends to create long posting lists. For example the word for or while appears a lot in most code. This tends to hold true for a LOT of terms you might want to search for. So you end up with a lot of the lookups for being a hundred million terms long. The only feasible way for that to work is distribute it across your cluster.

I also tried implementing a trie using the above numbers and some sample data, and my goodness the Go GC really did not like it, taking seconds to walk the pointers. It also took a lot more memory than I would have thought and ended up filling my laptop’s RAM before slowing down and being killed by me. It’s possible a Adaptive Radix Tree would reduce this but I doubt it would be enough to fit conveniently in RAM.

As mentioned, there are techniques to reduce the size of the posting list. Elias-Fano being one of the most well known, and Progressive Elias-Fano being perhaps even more efficient than bit signatures in terms of storage size. Also you still need to keep the posting list in a skip list, which is a data structure I have never written before, and seems like more complexity than I am willing to commit to.

So that leaves me with bit signatures from my original choices to implement. Which is the one I wanted to implement anyway even if I didn’t use them because they sound so interesting.

Bit Signatures Background

So there is a bit of background reading needed here. But in short, you use a bloom filter which is a space efficient way of saying something is not in a set or might be in a set. The other useful thing about bloom filters is that they grow linearly to the benefit you get from the length. This means as you make it longer, you drive down the false positive rate. Neat!

Before you email me about ribbon or xor filters, yes I am aware of them, I have read the papers on them, and looked through the code, but I am not comfortable enough to write my own implementation of them. Nor am I certain I can use the algorithms from bitfunnel against them. If you can prove it works to me with some source code I will be very happy to investigate.

One of the things I was most curious about was how many bits Bing used for the bloom filters in bitfunnel. While it’s entirely dependent on how large the documents are (since large documents have more terms) just having an idea helps when it comes to guessing. It took a while for me to pick it up but it was mentioned that they are around 1500 bits.

Using our guesstimate of 1320 unique trigrams, we can use the following calculator https://hur.st/bloomfilter/ to determine how large a document would be in our index.

Going with 1320 trigrams and a 1% false positive rate we get 12653 bits or 1.5 KB per document to store the index. That’s an impressive space saving there.

So back of napkin, 12653 bits per filter times 200 million then converted into gigabytes,

12653 * 200000000 == 2530600000000 == ~316 GB

Ok that’s still not going to fit totally into my RAM budget unless I scale out and half the index per machine with what I am using now. However the searchcode machines have been running for a while, I could look at getting some new ones and get more CPU/RAM to boot! Incidentally this is exactly what I did. I replaced all of the machines searchcode was running on with a 16 core 128 GB RAM machine.

Also if we make the guess that not all documents will have 1320 trigrams, we should be able to cut this down to something that fits in memory. Especially if we add some sort of page rank for the documents we want to index.

In reality putting everything into memory isn’t the universal panacea to improving performance that many think it is. CPU’s are fast, very fast! But getting data to them is comparatively slow. The “feed the cores” problem is why memory bandwidth is important for certain workloads. Stuffing your index into RAM might be one of those problems if for instance you needed to inspect most of the index, which bit signatures if done in a naive way. I think the CPU’s in searchcode have something like 40 GB/s memory bandwidth, so even if I was able to get the whole index into the 40 GB I want to use it would still take over a second to scan. Thankfully there are ways we can cut down the memory access which we will discuss later.

Anyway in terms of space we have a reasonable winner, and after reviewing how bitfunnel worked I was just itching to write a version of it. After all, there are only so many technical papers you can read about something before wanting to put the ideas into practice.

I am not going to write about bloom filters or how to implement them. I covered this in it’s own post which you can read if you are so inclined https://boyter.org/posts/bloom-filter/

Bit Vector Rotation

One of the things you can do to large bloom filters to improve performance is rotate the bit vectors.

This took me a bit to understand because all the examples used in bitfunnel were done using the same number of documents to vectors. Here is an example of it in ASCII which makes more sense… to me at least.

Consider a bloom filter with the following properties.

- 3 documents.

- 8 bit vector or bloom filter.

- Single hash function, so each term added is hashed once and flips one bit.

Normal view, where we have documents as rows and the columns contain the bloom filter.

document1 10111010

document2 01100100

document3 00100111

Rotated view, where we have terms as the rows and columns are for a single document.

term1 001

term2 101

term3 011

term4 000

term5 100

term6 110

term7 010

term8 100

So when you search for a term such as “dog” you hash that term, and fetch that row. So assuming it hashed to the 5th bit we would know that row 5 would be the one to look at and that document1 potentially contains dog.

Working with two or more terms is just as easy. Assuming you have “cat dog” where cat hashes to term 2, you get rows 5 for dog and 2 for cat.

101

100

Then you logically & them together and look for which column remains set.

101 & 100 = 100

Now the above confused me for a while. In your normal view the row is constrained by the size of your bloom filter, so it’s fixed to 1500 bits or something for bing. But the number of documents is unbound. So if flipped means you have these huge million/billion long rows to worry about. The trick I implemented is to restrict the number of documents per what I called a “block”. If you restrict it to 64 documents you all of a sudden can store everything using 64 bit integers in a list of whatever works out to be the best size for your bloom filter.

We also have an idea about how optimal this can be based on the talk from Dan Luu. Where the above with the other tweaks gives about ~3900 QPS from a single server with 10 million documents. He mentions being close to that as well on their production system. 3900 QPS means about 0.2 milliseconds to process a query. Keep in mind that bitfunnel also uses higher rank rows to improve performance and it is written in C++ which probably helps.

Considering I am planning on storing 20x the documents mentioned in the talk, and am also working in a far slower language compared to C++, I’d be happy if I can get down to 20 ms for each query, which seems doable. I suspect that most of it comes down to memory bandwidth. The CPU I use as mentioned has about 40 GB/s bandwidth. As such avoiding scanning all the memory is the main thing I need to worry about.

The other thing that’s really useful to note is that the number of hash functions per term added varies. You hash rare terms more than common terms. This reduces the false positive rate for rare terms. You can find details about this here https://www.clsp.jhu.edu/events/mike-hopcroft-microsoft/ The technique itself is known as a “frequency conscious bloom filter”.

I did the same thing in searchcode. I ran over all of the source code I had calculating the most common trigrams. On system startup searchcode loads these terms into memory and uses them to determine the number of hashes any trigram needs before being added to the index. Because trigrams tend to have more repeating words and less dimensionality than normal words we don’t need any more than 3 hashes to achieve a good result based on my tests. The function to determine this looks like the below,

func DetermineHashCount(ngram string) int {

hashCount := 3

v, ok := termTreatments[ngram]

if ok {

weight := float64(v) / float64(highestTermCount) * 100

if weight >= 5 {

hashCount = 1

} else if weight >= 2.5 {

hashCount = 2

}

}

return hashCount

}When called with a trigram it returns the number of hashes needed before adding the trigram into the filter.

With the above done I was able to build out the index.

The index itself is built on the core ideas of bitfunnel which was developed by Bob Goodwin, Michael Hopcroft, Dan Luu, Alex Clemmer, Mihaela Curmei, Sameh Elnikety and Yuxiong He and used in Microsoft Bing https://danluu.com/bitfunnel-sigir.pdf. For those curious the videos by Michael are very informative, you can find the links to them here and here. Watching those alone will give you enough information to implement your own index itself.

The index is a 100% non-positional memory index, based on bloom filters, sharded by document size, named caisson since it’s designed to work under high pressure. Nothing is persisted, and on process crash the index is rebuilt. This sounds horrible until you remember one of the constraints, and that as a free service if nobody is able to search everything for an hour or two that’s fine.

The index is split into shards which are further split into 8-12 buckets. Each bucket has a differently configured bloom filter, designed to save space while preserving a target false positive value. A result of this is that buckets contain documents of similar length with the smaller bloom filters getting shorter documents.

When a document is enqueued to be indexed, it is routed to the appropriate shard, and the number of distinct trigrams in that document is calculated. This is important because there is a relationship between the number of trigrams and the number of bits set within the bloom filter. In order to avoid wasting space, a bucket is chosen which gives an appropriate amount of bits set, where the idea is to lower the false positive rate without wasting memory. Documents are truncated to ensure they don’t overfill bloom filters, so even if searchcode is working with 1 MB file, only the head of that file will be added to the index, without overfilling its filter.

┌──────────────────┐ ┌──────────────────┐ ┌──────────────────┐

│ caisson ├─┬▶│ caisson shard ├┬─▶│ bucket-1 │

└──────────────────┘ │ └──────────────────┘│ └──────────────────┘

│ │

│ │ ┌──────────────────┐

│ ├─▶│ bucket-2 │

│ │ └──────────────────┘

│ │

│ │ ┌──────────────────┐

│ └─▶│ bucket-3 │

│ └──────────────────┘

│

│

│ ┌──────────────────┐ ┌──────────────────┐

└▶│ caisson shard ├┬─▶│ bucket-1 │

└──────────────────┘│ └──────────────────┘

│

│ ┌──────────────────┐

├─▶│ bucket-2 │

│ └──────────────────┘

│

│ ┌──────────────────┐

└─▶│ bucket-3 │

└──────────────────┘

Once the target filter is picked, the document is added, with the bits in the bloom filter being flipped right to left. It also saves other details about the document such as what language it is, its source and its size.

In memory the buckets look like the following, which is just a huge slice of 64 bit integers one after the other. These are organised into blocks, consisting of as many integers as there are bits in the bloom filter. So a 512 bit bloom filter would have 512 integers in each block, with each block containing 64 documents.

When the 64th document is added filling the left most bits, another block is appended onto the current one, and the bits start filling right the left again.

┌──────────────────┐ ┌───────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ bucket │───▶│ │

└──────────────────┘ │ 0011100000000000000000000000000011010010000000000000010000111111 │

│ 0000100000000110001000000000000000000000001010001000001000000000 │

│ 0010000000000000000000000000000001010001111111110000010100111111 │

│ 0000100011010000000000000000000000000000001010001000000110000000 │

│ 1100011000000001111111010100100010000000000000010000000000100100 │

│ 0000000000000000000000000000000000000001111111110000000000000000 │

│ 1000011000100001111111010100000010000000000000010000000000100100 │

│ 0000000000000000000000000000000000000001111111110000000000000000 │

│ 0000000000000010000000000011000000001000000000000000000000001000 │

│ 1111111000000000000000000000001000010000010000000000000000011000 │

│ 1111111111111111000000000011000000000000000000100010000000000000 │

│ 1111111000000000000000000000001000010000010000010000000000001000 │

│ 0000000000000000000000000000000000111110000000000000000000000000 │

│ 0000000001100000110000001000000000000000000001000000101001000000 │

│ 0000000000000000000100000000000000111110000000000000110000010000 │

│ 0000000000100001110000001000000001000000000000000000101001111111 │

│ │

└───────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘

Searches against the index have the query term and facets passed in, where they are run in parallel across each shard, with the shard itself determining which buckets should be searched and in what order. When a search runs it returns all of the possible document id’s that match, the number of matches, the document size and some other metadata that is required. All of the values from each shard are joined together, and then ranking is applied.

Once ranking is applied searchcode starts looping through the results, looking to find true matches. Because of the use of trigrams and the bloom filter, there are always some false positive matches that must be removed. This process iterates until enough results have been found, at which point the matching lines are scanned for and the results returned. Interestingly, finding candidate lines to present to the user is by far the slowest part of the application.

The core search algorithm is beautifully simple, looking like the below with a fixed 2048 bit bloom filter.

func search(queryBits []uint64) []uint64 {

var results []uint64

var res uint64

for i := 0; i < len(bloomFilter); i += 2048 {

res = bloomFilter[queryBits[0]+uint64(i)]

for j := 1; j < len(queryBits); j++ {

res = res & bloomFilter[queryBits[j]+uint64(i)]

if res == 0 {

break

}

}

if res != 0 {

for j := 0; j < 64; j++ {

if res&(1<<j) > 0 {

results = append(results, uint64(64*(i/2048)+j))

}

}

}

}

return results

}After I put everything together there was a lot of testing and validation against the data set searchcode was going to hold. With a bit of tweaking I was able to index somewhere around 160-200 million documents in the RAM budget I allowed, with an average search time of 40ms across it. Good enough for me to move onto the next thing.

Facets

Previously searchcode had filtering down by language, repository or source. These are calculated with values for each search. Also this turned out to be really painful. Working with 200 million of anything is a serious pain. It was easily the most annoying bit of code I ran into that was just not fast enough no matter what I did.

Given our 200 million documents, how long does it take to determine what languages are in the result set?

// hold the facet in memory. Assume 300 languages and randomly assign each document as to one

codeFacet := []int{}

for i:=0;i<200_000_000;i++ {

t := rand.Intn(10)

// attempt to distribute them such that some are more common than others

if t == 0 {

codeFacet = append(codeFacet, rand.Intn(10))

} else if t < 3 {

codeFacet = append(codeFacet, rand.Intn(50))

} else if t < 7 {

codeFacet = append(codeFacet, rand.Intn(100))

} else {

codeFacet = append(codeFacet, rand.Intn(300))

}

}

// lets simulate a search of which found 1 million matching documents in our result set

filters := map[int]bool{}

for i:=0;i<1_000_000;i++ {

filters[rand.Intn(200_000_000)] = true

}

// now lets count how many times we see each "language" filtered by the search

// we start timing from here

realLangCount := map[int]int{}

for i:=0;i<len(codeFacet);i++ {

_, ok := filters[i]

if ok {

realLangCount[codeFacet[i]]++

}

}So I tried the above, and it takes roughly 11 seconds to aggregate. That’s not going to work. Especially as it pegs a single core while doing it. It uses about 2 GB of RAM as well which is fine for our purposes, as 3 such lists for each of the current filters will be around 6 GB in total when implemented (unless we can mush them into the same list or something).

I was curious to see how much Go was the problem. So I wrote a braindead implementation in Rust. Because no blog that mentions Go is complete without some comparison to Rust either directly or via the comments. Note my Rust is poor at best, but I then copied my implementation to Go to see how each fared. These aren’t 100% directly comparable, but I am not trying to do that, i’m just seeing how a naive implementation in each run.

package main

import (

"fmt"

"time"

)

func main() {

// hold the facet in memory where we assume 300 languages and randomly assign each document as to one

codeFacet := []int{}

for i:=0;i<200_000_000;i++ {

codeFacet = append(codeFacet, i%300)

}

// lets simulate a search of which found 1 million matching documents in our result set

filters := map[int]bool{}

for i:=0;i<1_000_000;i++ {

filters[i%200_000_000] = true

}

start := time.Now().UnixNano() / int64(time.Millisecond)

// now lets count how many times we see each "language" filtered by the search

// we start timing from here

realLangCount := map[int]int{}

for i:=0;i<len(codeFacet);i++ {

_, ok := filters[i]

if ok {

realLangCount[codeFacet[i]]++

}

}

fmt.Println("time:", (time.Now().UnixNano() / int64(time.Millisecond)) - start, "ms")

}use std::collections::HashMap;

use std::time::Instant;

fn main() {

let mut codefacet = Vec::new();

for n in 1..200_000_000 {

codefacet.push(n % 300);

}

let mut matching_results = HashMap::new();

for n in 1..1_000_000 {

matching_results.insert(n % 200_000_000, true);

}

let start = Instant::now();

let mut facet_count = HashMap::new();

for codeid in codefacet.iter() {

if matching_results.contains_key(codeid) {

facet_count.entry(codeid).or_insert(0);

*facet_count.get_mut(codeid).unwrap() += 1;

}

}

println!("time: {} ms", start.elapsed().as_millis());

}Followed by a quick compile and run,

$ go run main.go && cargo run --release

time: 11205 ms

Finished release [optimized] target(s) in 0.03s

Running `target/release/rusttest`

time: 8412 ms

Interesting. Rust is faster as you would probably expect, but not so much faster that you still wouldn’t have a problem.

NB A kind reader emailed me about the above, and supplied a modified version of the Go code. Specificly changing one line to use empty structs for allocations and not bool, so,

// lets simulate a search of which found 1 million matching documents in our result set

filters := map[int]struct{}{}

for i:=0;i<1_000_000;i++ {

filters[i%200_000_000] = struct{}{}

}Which speeds up the Go version a bit. In addition, I tried this with the latest version of Go 1.19 and it sped up yet again from my previous attempts running faster than the Rust version. I have no idea how to do a non allocation version in Rust, but even without on my machine Go is now faster for this task. Remember to upgrade your compiler people! Still not fast enough for my purposes, but hey free performance is always good.

$ go run 1/main.go && go run 2/main.go

time: 6383 ms <-- non allocating runtime here

time: 6783 ms

For comparison a mate of mine tried C++ with -O3 compile option and got a runtime of around 2 seconds. Not sure what voodoo it’s doing to achieve that. We compared the output to ensure it was the same and it was. Our best guess was it unrolls the loop to fit the CPU/RAM best. This is rather annoying because if I were using C++ I would be very close to being done with that sort of performance.

How do Google/Bing do this? Turns out they don’t. For a start they don’t have facets over the web index. Enterprise search engines such as sphinx/manticore/elasticsearch/lucene do. Time to go code spelunking! See how someone else solved the issue. The Java codebases are pretty annoying to read (I actually like Java but got bored trying to understand it) and my C++ is not good, but it looks like they rely on straight line brute force speed. They then shard the index to keep that performance. What about Bleve? it’s written in Go! Let’s have a look at how it works.

Looking at index_impl.go (around line 495) shows how the facets are constructed if on the supplied query. Turns out it’s doing roughly the same thing I was. A loop putting things into a map. I don’t know what I was expecting, but it would have been a nice find to see some fancy way of speeding this up. I guess it means you cannot realistically do filters using Bleve for 200 million items on a single core. Or you can, but be prepared to wait a bit for it to finish.

So what if we estimate? Turns out this is how Bing and Google work anyway. Not for facets but for search in general.

Don’t believe me? Try searching for a fairly unique term. In my case I chose “boyter” on both. Google says it has 590,000 results for this and Bing says 107,000 results. However if you try to page though… Bing caps out on page 43 (interestingly Bing does not have a fixed number of results per page, possibly due to that false positive issue of bitfunnel) with 421 results. It shows more pages but won’t let you access them. Google by contrast caps out on page 16 with 158 results.

So as a result I removed the facet counts. Facets are still implemented, but you don’t get to see how many results of each there are. This is something I do want to add back in at some point though, so watch this space.

Ranking

What about ranking?

We don’t actually need anything too fancy for searchcode. I doubt anyone is trying to game its search results, so spam isn’t an issue nor is keyword stuffing. Anything that affects the ranking in a negative way can just be removed from the index. While web search engines tend to use thousands of signals in order to know how to rank, searchcode can get by with something simple such as TF/IDF or BM25. Thankfully I have already implemented both (including the Lucene TF/IDF variant) for other projects, so a little copy paste and done.

Sourcegraph, another code search engine, had Steve Yegge write about this actually, https://about.sourcegraph.com/blog/new-search-ranking however it was posted very recently and is included here since its relevant, but did not impact anything I have done.

The question being can my implementation of it work fast enough over millions of matches. At what point is it too slow and eating into our 200 ms target time budget?

Thinking about this did raise an interesting question. If you search for a common term such as “boom” on Bing or Google, both report over 50 million results. However the search still comes back instantly. Google (at time of writing) claims the term exists in 548,000,000 results. That number as I already established is a lie, so let’s assume it actually looked at 100 million. Given what we know about documents, about 500 unique terms and it takes 2504 bytes to store the terms of that document in the index, we can determine how much RAM they inspected to get this number.

2504 bytes * 100000000 = ~250 GB

This roughly works out to be about 250 GB of data you need to filter through and then sort. Let’s say Google actually did the full range it reported that works out to 5x that result so 1.2 TB of data.

Now is it even possible to rank and sort that much data in under 500 ms which Google returns in?

The terasort benchmark allows us to at least get an idea about this. It’s a benchmark based on sorting 1 TB of random data as quickly as possible. I tried to find a recent result for this, but this https://www.wired.com/insights/2012/11/breaking-the-minute-barrier-for-terasort/ from 2012 shows that Google was able to sort the 1 TB of data in 54 seconds, using 4000+ CPU cores.

Let’s assume it could be done in half the time with current CPU’s. So 1 TB in 27 seconds, then let’s do it for the 250 GB of data divided by 5 gives us 5.4 seconds. At this point I am fairly skeptical that Google is actually ranking the entire set. Even if they threw 5x the servers at it. Plus think of the cost. It was said that at the time the terasort record cost about $9. Let’s assume it gets massively more efficient over time and say that it costs $1 for every search on Google for a common term to rank.

Apparently Google did over 2 trillion searches in 2016. They also made about $90 billion dollars that same year. Pretty clearly that isn’t going to work out, even in silicon valley where you make your losses up with volume. You really need to be processing that sort for fractions of cents.

It’s a similar story on Bing. Even if it is losing money for Microsoft I doubt it’s losing money that quickly. While they have multiple machines which might solve the time issue, I doubt any company is going to let customers burn 10c to $1 per user action, unless also charging $2 for that action.

So how do they do it? I only have theories as I have never worked on a commercial search engine but I suspect there is some sort of pre-ranking going on or caching of some query terms with ranking, and on top of that smaller set is the actual ranking which then includes your user data and whatever other signals they use in the secret sauce. This makes some sense really because while PageRank is apparently not the most important signal used today some form of it still runs inside google, and pagerank is very much a pre ranking algorithm.

Tangent. But I suspect that some of the reason that Google’s search isn’t as good as it used to be is the above. So much pre ranking goes on that when your query comes along you just get a custom ranked version of what was already pre ranked. As such it’s less about your query now and more about those pre ranks. If true I don’t think the problem is going to get better anytime soon as the web keeps growing exponentially making it almost impossible for a new player to enter the market with a new algorithm. Meanwhile Google has no real reason to adjust its algorithms since it’s making more money than it knows what to do with. The only thing that might change this is if someone comes up with seriously clever and is able to index at a cheaper price. Which I guess is what Cuil did, but they didn’t get the ranking done very well.

So back to my problem trying out on my local machine a rank and sort for 1 million documents. Pre-ranking sounds reasonable, but we aren’t talking about hundreds of millions of documents here. We just aren’t in the same level of scale. For 1 million matching documents ranking takes 80 ms and sorting 264 ms. That’s without attempting to make it go any faster, on my first cut of the code.

Ranking is the easy one to speed up. We run it in parallel. That brings it down to 10 ms for 1 million documents. We can also flip from Lucene TF/IDF to pure TF/IDF for a small saving, changing the line

weight += math.Sqrt(tf) *idf* (1 / math.Sqrt(float64(results[i].wordCount)))to

weight += tf * idfwhich for very large cases saves a few ms of time. It reduces quality a bit, but generally if someone searches for for there isn’t anything useful to show them, so it’s probably acceptable to cut some corners there in the interest of speed.

Now for speeding up the sorting. There are faster sorting algorithms than what Go ships with as I mentioned. Some do so by trading memory for speed. But first let’s try doing something else. The ranking algorithm returns a float with 0 being the lowest possible rank and the highest some number way higher than than. If we iterate through the slice and find the highest number, we could then loop though looking for ranks close to that, shove that into a new list and sort that. The reason this works is that looping over a slice in Go is really fast.

With that in place we know that the top score might be say 43.01 or some other value. We can then iterate over our list looking for values higher than say 95% of this value. Then keep reducing that percentage size till we get whatever count of items we need.

This has the double bonus of making the list mostly sorted in reverse order, which should help with speeding up the final sort as well depending on what sort algorithm Go uses under the hood. I am assuming insertion sort for short slices and timsort otherwise, but should probably verify that assumption.

Regardless, this new idea is actually fairly easy to code.

var topResults []*doc

aboveScore := (maxScore / 100)* 95

for len(topResults) <= 1_000 {

for i:=0;i<len(results);i++ {

if results[i].score >= aboveScore { // must be >= or infinite loop here, so be careful!

topResults = append(topResults, results[i])

if len(topResults) >= 1_000 {

break

}

}

}

aboveScore = aboveScore * 0.9

}The results? Well for 5 million documents, the ranking takes about 80 ms. The finding of the top results and sorting them takes 26 ms. Looks like the sorting issue is solved. Also this leaves us with a huge time budget for putting additional ranking on top if we want.

In fact after all the above and some other tweaks I was able to get it ranking 50 million documents in 800ms and the sorting and selection done in under 30 ms.

The reality is though that I am likely to cut off any further processing if we get something like 100,000 or something documents. It’s not like I let you page through them anyway. Also at 100,000 documents on my laptop I can rank, collect and sort in ~3 ms which is probably fast enough for my purposes.

The last step for ranking I implemented is some “page rank”. There is nothing fancy done here

Other Tweaks

So as mentioned I moved searchcode to a single machine holding the index. When I first wrote searchcode I ended up splitting it apart, into crawling processes and such, talking though queues. I have more or less reversed this entirely and now everything is in one large binary. I am able to shard simply by adding another server and splitting the data indexed should I choose, but I can also scale up easily.

I also copied the stackoverflow method of caching. Inside searchcode there is a level 1 cache which runs in memory. This is checked for cacheable values, and if not found it falls back to the level 2 cache which is redis. I also added a disk cache for things like the sitemap, just to save on the processing time.

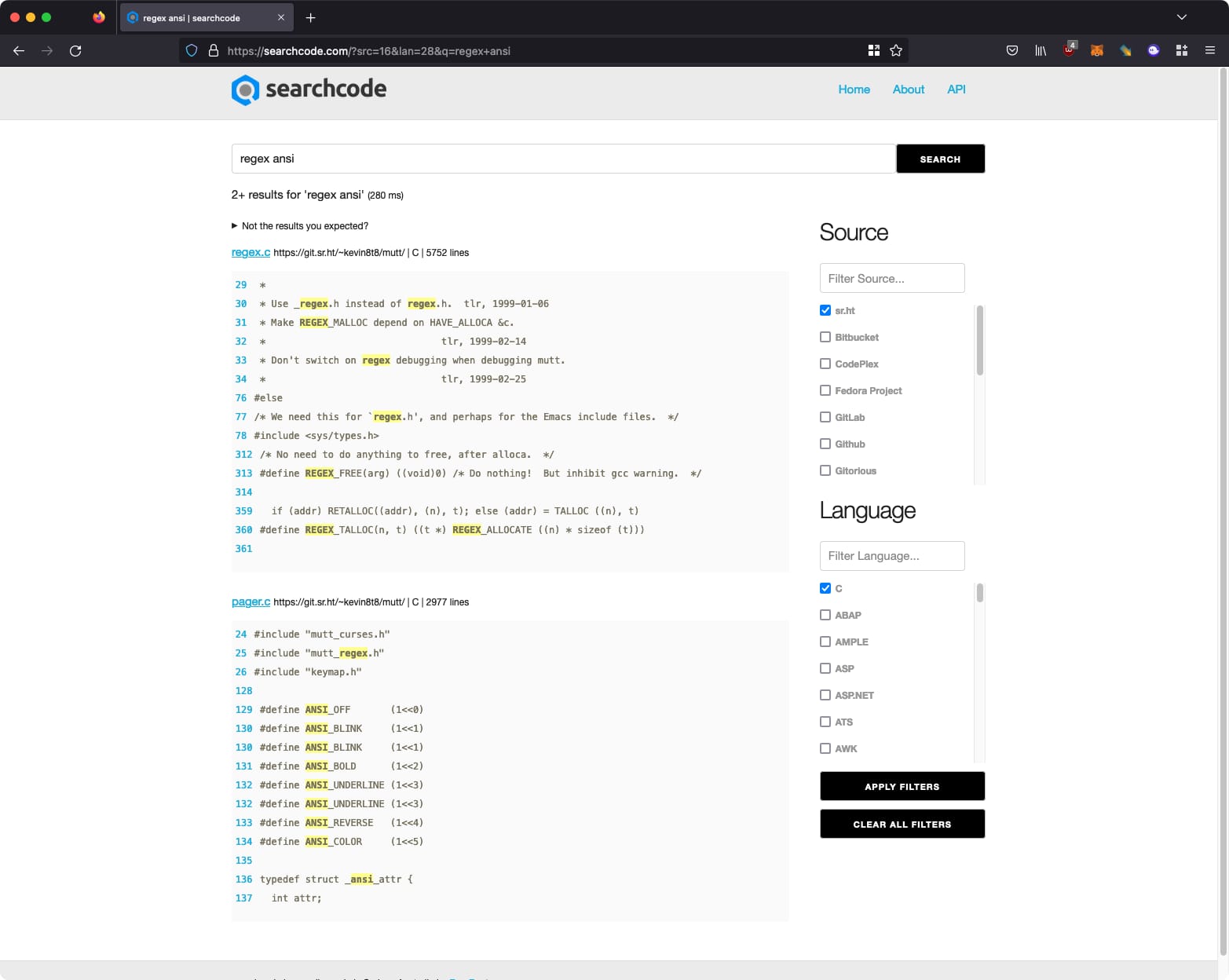

Since github/sourcegraph and other code search engines have done a great job with github, I turned my attention to the other code repositories. So you can expect more attention for sr.ht, codeberg, bitbucket and other sources of code in the future. If developers from any one of those repositories would like to work with me let me know, i’d be happy to index your code.

Duplicate code detection has been improved in searchcode. This is important to ensure we don’t return hundreds of the same result. This is done by checking how popular each repository is (github stars etc…) and then checking if code was copied, and then marking the most popular one as the source of truth.

Problems / Improvement Opportunities

So what has been implemented is not perfect. In fact it is far from it. There are things I would like to improve, and I have some of them listed below.

The first is that some search queries contain only common trigrams which produce a huge amount of results, but when joined together form a word or match we are looking for that are very rare. Because searchcode is non-positional, the only way to confirm if something is a match is to actually check it. An example of this that I ran into in testing was a search for jude law which in early tests would take 10’s of seconds to return. I spent a lot of time optimising around this particular case, but it still exists. Another example of this would be searching for ripgrep which annoyingly has some of the more common trigrams, however the moment you add its author ripgrep BurntSushi or restrict it down to the language ripgrep lang:rust you get results as expected.

As mentioned in the above, I don’t have the full counts of facets available. I was unable to find a way to calculate these accurately, and in the interests of getting things out the door decided to drop the counts entirely. It is on my list of things to improve.

No paged results. I removed the ability to page results in favor of a single page of 100+ results. I am planning on bringing pages back at some point though once I get the time to put this back in properly.

It’s code I wrote… so naturally there have been a few crashes since it went live. Thankfully all easy fixes, but not exactly my finest hour. A few came down to off by one errors when searches were running. This surprised me because I had been indexing and testing for months before the release. However it came down to a very unlikely race condition, which became far more likely at the scale searchcode operates at. In short, when adding to an index, there was a brief chance for the result to match, but missing some details such as what language it is, that caused access to a portion of the slice that was not written yet.

The second was more annoying. I started getting out of memory kill events in the syslog. This was especially worrying because I had explicitly written searchcode to never exhaust the total amount of system memory. My theory was that due to the high level searches running I was bumping into a RAM issue, which never surfaced in regular testing.

Thinking about our requirements and constraints. One thing to consider early on is how to do searches in your index. You have two main options. The first is to allow searches in parallel and the latter is to not do that. However the choice between might not be as simple as you would think. It also greatly impacts the design of the system.

Most would think, of course, do it in parallel! Process in parallel so that way people wait less. But do they? As more searches come in, the average time for each search goes up. Consider the situation that 10 people all search at the same time. Lets also assume that each search takes 1 second. Given limited resources which is true for most cases it means all 10 searches are shared across the system. As such everyone gets 1/10th of the system to search with and end up waiting 10 seconds for a result.

However, consider doing it in serial. While all came in at once only one can go first, and that person’s search returns in 1 second. The second was waiting on the first and their search took 2 seconds. The third takes 3 seconds etc… till the last one who had a 10 second wait. Which is the better result? I would argue the latter.

There are a few other advantages to doing your searches in serial. You can attempt to consume all the resources you have at your disposal to give a good result, you don’t have to worry about memory issues since you should know how much memory you need at any one time.

So as a hail mary I added a counting semaphore over the search function in order to control memory usage. This would allow some level of parallelism. Thankfully this is very simple to do in Go.

var sem = make(chan bool, 5)

func doSearch() { // only 5 instances of this function can run

sem <- true

defer func() {

<- sem

}()

}With that added I restarted the service, waited for it to get the level of scale that was crashing previously and thankfully it resolved the issue. The result was finally a stable service. Hurrah!

Well if you got this far you now know how every search in searchcode.com works. You are also pretty hardcore, and as such might be interested in an add on service I want to offer. In short you can use searchcode to check if any code in another codebase has been copied, and as such is potentially a licence violation.

I supply a binary file, you point it at your code, it produces some non-reversible hashes, which it uploads. The hashes are then checked against every line of code searchcode is aware of and lets you know if it finds copied functions. Oh and the binary file? Yours to keep, and you can use it to find duplicate content in your own codebase, without ever talking to searchcode.

If that sounds interesting to you, feel free to contact me using the methods listed below.