A short time ago one of the more interesting blog posts (to me anyway) about cache eviction popped up on Hacker News which prompted me to post the following comment.

Love reading this. It has always been one of those interesting things I kept in the back of my mind in my day to day.

I was very excited when I actually got to implement it on a real world project.

I was writing a scale out job which used ffmpeg to make clips of video files. To speed it up I kept the downloaded files (which could be 150 GB in size) as a local cache. Quite often a clip is made of the same file. When the disk was full (there was a separate disk for download and clip output) selected two of the downloaded files randomly and deleted the older one. Loop till there was enough disk space, or no files.

It’s something I thought I would never actually get to implement in the real word, and thus far is working very well, the caching speeds things up and the eviction seems to avoid too many cache misses.

Since I have a policy of trying to keep any content I write on-line mirrored on this blog I thought I would take the above and flesh it out a little.

As mentioned I remember reading this some time ago. It literally was something I considered very cool, but since day to day I don’t work on redis which uses a modified version of the algorithm or some other caching solution I figured it was something I would never get to implement in a real world project.

However that turned out to not be the case! There was an application I have been working on for a while now which was able to use this technique. The application in question is a large archive of video/audio/image content which holds about 900 TB of data collected over the last century. Quite often the video files in the application are in production grade formats such as MOV and MXF and with 2 hour programs/films inside the archive they can in excess of 300 GB in size. Due to the woeful state of the internet in Australia and the requirement that this archive work nationally bandwidth use is a real problem. Users in regional areas simply are unwilling or unable to download a 300 GB file, especially when quite often they only want a 5 minute snippet or clip taken from the middle of it.

The application is deployed inside AWS and while their video processing suite using Elemental is very good, for taking a snippet/clip out of a file it is not currently ideal. The reason being that it will actually transcode the file during this process, which increases the cost and slows down the process. I have let AWS know that this is why Elemental is not being used in this case and I suspect in time they will offer something that can do this.

The reason why the transcode was undesirable is that the users can be quite picky about the formats and as such it was easier to preserve the original format then try to get everyone from all of the different groups to agree on one format to rule them all.

As such the solution proposed was to use ffmpeg. It could pass through the file preserving the container and all the other embedded metadata such as data streams. The actual solution implements two ffmpeg commands, the first trying to preserve all information and the second as a fallback in case of failure with the addition of stripping out data streams. This was due to some formats causing it to fail, and we took the approach that even if not ideal at least it worked, and even if you lost some information and you can always download the full file as a failsafe.

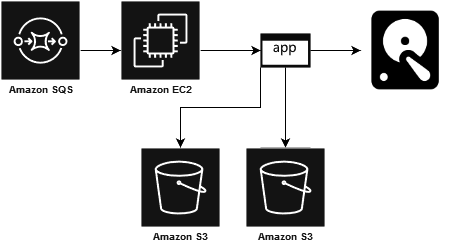

Since the solution called for using ffmpeg and dealing with very large files we designed around a resilient queue using SQS and small scale out machines using T3.small AWS instances with a large amount of disk space. The reason for T3 instances is the burst-able network performance. The ffmpeg command as written does no transcoding so it actually uses very little CPU. The only real CPU usage in production is when the network bursts hence the choice of small instances. We have observed these instances bursting to 6 Gbps in production so network usage is the real bottleneck in this solution. The input files are stored in S3 and transfered to local disk and the clip when finished is pushed into S3 again.

We did look at talking directly to S3 using ffmpeg, but this would not have allowed caching, and we found that for MOV files we needed to download most of the file anyway in order for ffmpeg to work correctly so this was not a great option.

Due to nothing like this having been implemented at the organization before, we took a guess and assumed that users would want to make multiple clips from the same file. As such it made sense to cache the files we downloaded. However this came with one issue, which is that because we attach local storage to the instances we need to have some way to clean up disk to ensure that we have enough space to download the original file, and to ensure we have enough space for the clip output.

This was where the 2 random disk caching eviction policy came up. It is also when I did a few fist pumps because I finally got to implement something I had always wanted but never had a reason to do. The code for it is actually fairly simple, and written using Go.

// Given a filePath, target size and required size this method will

// delete files in that path until it has enough space, or there are

// no files left to delete and return an error.

// Uses the cheap but effective 2 random choice eviction algorithm for this

func ClearSpace(directoryPath string, freeSpace uint64, requiredBytes uint64) error {

// Required to ensure that the random choice is appropriately random

rand.Seed(time.Now().Unix())

for freeSpace < requiredBytes {

// Get the files. The method does ioutil.ReadDir(directoryPath) and returns all files as a slice

fileList := GetFiles(directoryPath)

// If there are no more files to remove then we don't have enough space

if len(fileList) == 0 {

return errors.New("cannot free enough disk space")

}

// To make space pick two random elements from the list and then

// delete the oldest one

one := fileList[rand.Intn(len(fileList))]

two := fileList[rand.Intn(len(fileList))]

if one.ModTime().Nanosecond() <= two.ModTime().Nanosecond() {

os.Remove(path.Join(directoryPath, one.Name()))

freeSpace += uint64(one.Size())

} else {

os.Remove(path.Join(directoryPath, two.Name()))

freeSpace += uint64(two.Size())

}

}

return nil

}The only tricky part of the above was determining the disk space available which is sadly is not possible in a cross platform way. The below achieves this but is POSIX only so it won’t compile for Windows. Since our targets were Linux machines this was deemed acceptable, and we could always go back and re-factor to add Windows support later if required.

// POSIX only and attempts to determine how much

// free space is left on the device given a path

func Free(directoryPath string) uint64 {

var stat syscall.Statfs_t

syscall.Statfs(directoryPath, &stat)

// Available blocks * size per block = available space in bytes

return stat.Bavail * uint64(stat.Bsize)

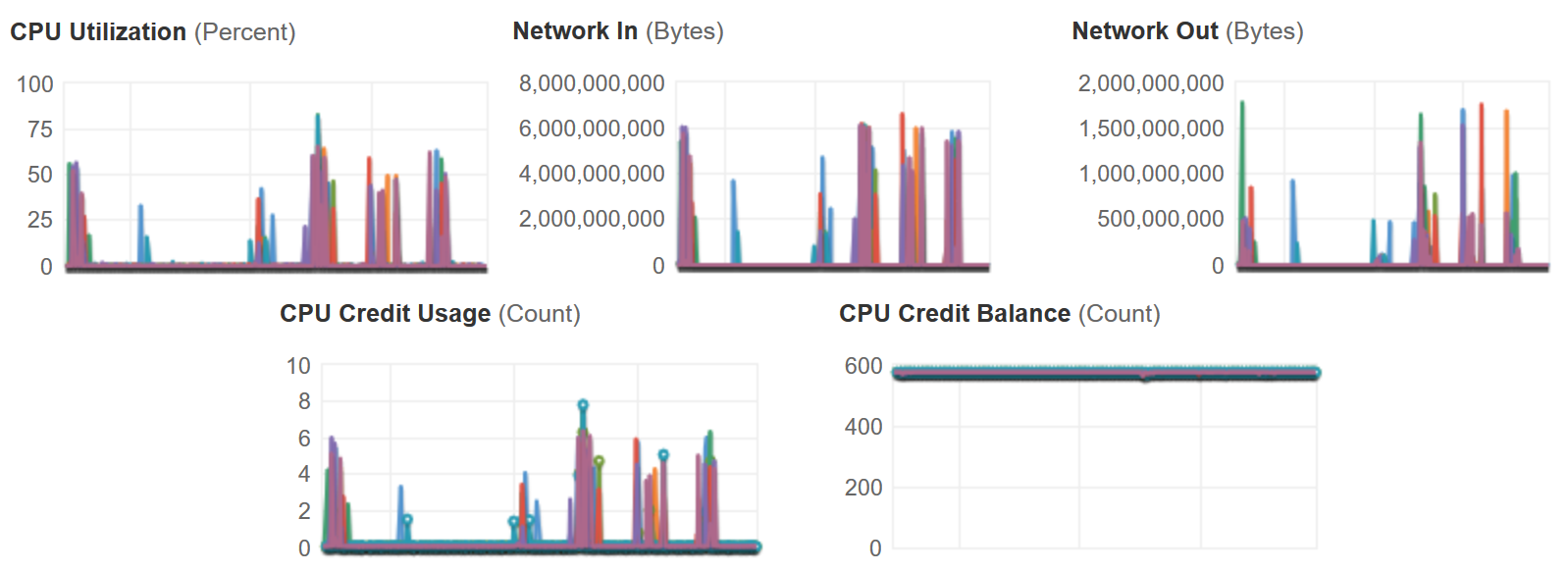

}The results of all of this? Well in production we currently have 8 running instances. They are busily processing away and I have included the interesting AWS metrics from monitoring below. The metrics are taken over the last week and in that time about 1000 clips have been processed. The only reason for so many instances is to ensure that if a clip is requested it is processed as quickly as possible.

We do have auto scaling on these instances based on the queue size but since the application was launched 8 has been more than enough instances, processing quickly enough and it has never scaled out. Note that the credits never expire from these instances making me think we could possibly drop to smaller instances if required, but since the average cost for each clipper is around $700 a year I doubt its worth the effort. It seems like a better idea at this point would be to drop the number of instances from 8 to 4.

In terms of times, the average time to process a clip is under 5 minutes so far. Most of the clips are being made from 300 GB files and from our logging the cache is working quite well and has saved over 200 S3 fetches.

For smaller files they are quite often processed in 30 seconds or under with the experience feeling almost instant for the end users. The instances being shared nothing will re-download files their neighbors so it is not an optimal solution but the reality so far is that the system works very well with a fair amount of praise from the users. I doubt we need to optimize any further at this point, but it would be possible if the number of clips became exponential. Some ideas would be having some smarts around how the queue works to ensure the cache is hit more often.

So thats the story. Finally got to implement something I have always wanted and proves the point that no random reading of technology solutions is ever without merit, even if they are not directly applicable to what you are doing today.